With regards to the economy, inflation is currently the major topic of conversation, this is true for both the general economy and for agriculture. The governments preferred measure of inflation, the Consumer Price Index (CPI), after being close to the Bank of England’s target of 2% for many years, looks set to exceed it by two or three-fold in the short term, forecasts of 6 – 10% currently abound. Recent events in Ukraine suggesting such high rates of inflation may not easily go away.

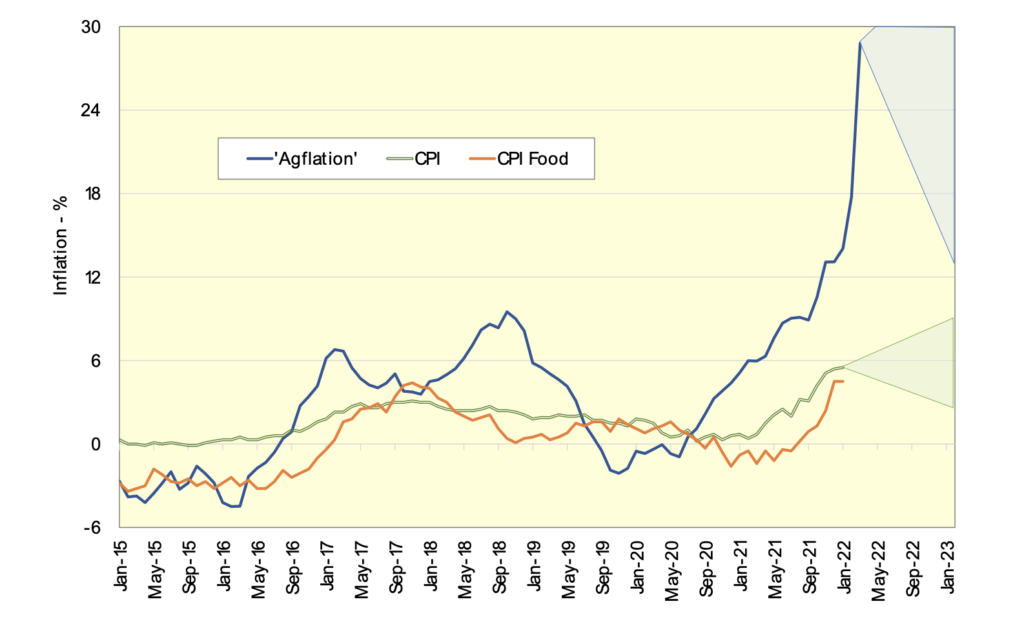

Andersons have calculated “agflation” figures based on Defra price indices for agricultural inputs, weighted for their overall value.

As can be seen from the graph below it is much more variable than general inflation due to linkages to commodity prices for things such as fuel, fertiliser and animal feed. Fuel and fertiliser prices tend to grab the headlines, but animal feed makes up almost 25% of the index and is the largest input used by UK agriculture in terms of its value.

‘Agflation’ – Price Changes 2015 to 2023

From the graph agflation rates in excess of 25% appear eye watering.

One of the major effects will be the quantum of working capital required to run farm businesses going forward with for example, the amount of money required to grow a hectare of wheat or fund a months worth of feed for a livestock enterprise, increasing very substantially.

Price volatility and the risks of trading have gone up significantly, meaning accessing this extra funding, whether from additional Bank lending or merchant credit, may not be straightforward. Merchants own credit terms are being squeezed, meaning they in turn may be much more cautious in what they are willing to lend to farmers and under what terms.

Farmers may well have to be more reactionary to secure available inputs at the best possible prices and the ability to pay for them there and then may also become more important.

The phrase “Cash is King” should perhaps be at the forefront of our minds at this time.

We have tried to offer some thoughts below on how farmers might deal with the three key inputs the to the sector; feed, fertiliser and fuel.

Feed

High feed prices have dramatically increased the pressure on producers to maximise their efficiency of use across all sectors.

In the ruminant livestock sector sheep are perhaps the least effected and those producers who have developed largely forage based systems look set to fair best. We still see high levels of concentrate use compensating for poor management this looks set to become significantly more difficult to justify.

With regards to beef cattle, squeezing out concentrates to the same degree as for sheep is more difficult but again, we still feed more concentrates, very often in the form of home-grown barley as the easy option in many systems. Monitoring liveweight gains, improving feed conversion efficiencies and the use of quality forages, whether grazed or conserved, continues to have great potential for many producers.

In the dairy sector, high input high output systems, typically involving all year-round calving, are the most exposed to agflation. Efficiency of feed use, knowing the cost of feeding for marginal litres and a suitably responsive milk buyer will be crucial to the profitability of these systems.

Forage based, typically block calving systems are less exposed to the current crisis and farmers, processors and retailers could all have much to gain from seeing how such systems might deliver an increasing share of UK milk production in the future.

In the intensive livestock sector, efficiency of feed use is even more important, being the major cost in these systems. If UK production levels are to be maintained, increasing levels of vertical integration appear essential as with production cycles being relatively short, if substantial losses are incurred, numbers are likely to fall very quickly.

Fertiliser

The UK currently uses approximately 1.5 million metric tons of chemical fertiliser per annum, around 1 million tonnes of which is nitrogen.

Chemical fertilisers have generally proved an excellent investment for farmers to date, with the cost of such fertilisers recovered several times over by the additional yield generated. In addition, the product has come in a form easy to transport, store and apply.

At current prices, businesses will be forced to challenge these previous norms before making what looks likely to be a very substantial investment in chemical fertilisers.

As a first step re visiting the recommendations in the Nutrient Management Guide (RB209) published by AHDB would seem essential.

Other things to consider may be:

- Ensure soil pH, P, K and S levels are optimal, imbalances here will result in poor utilisation of nitrogen, big gains can be made here particularly in many grassland situations.

- Assess field drainage problems, wet soils with poor drainage result in high nitrogen losses from leaching.

- Re appraise the inclusion of crops with a high nitrogen demand in the rotation, for example second wheats.

- Making better use of whatever slurries and manures are available, either home produced or imported, analyse their content, understand their costs in terms of price per kg of nutrient applied as compared with chemical fertiliser.

- Consider the value of nitrogen fixing crops such as peas and beans across the whole rotation, despite their often-lower gross margins.

- Can agri-environmental schemes be used to advantage by helping with the costs of incorporating nitrogen fixing crops such as clover into rotations.

- In many ruminant livestock situations, much more grass can be grown and utilised per kg of fertiliser applied through better management, such as avoiding compaction and adopting rotational grazing techniques.

- The use of clovers and legumes in grassland swards can replace synthetic nitrogen requirements particularly in less intensive situations, a reappraisal of the intensity of use, whether for grazing or cutting, may yield benefits.

Fuel

Red diesel is the major fuel used by most UK farming businesses.

Prices have generally been in the 45 to 65p per litre range over the last few years and whilst not insignificant, have not featured as one of the major overhead costs for most farm businesses, however the scale of recent price increases has changed this.

Being aware of how much fuel is being used and what the cost price increase means to the bottom line is a good starting point for all farm business.

If a combinable crop business uses 100 L of fuel per hectare tilled, a 10p per litre increase in the fuel price results in a £10 per hectare increase in costs.

The solution remains the same as it has always been, which is to limit fuel consumption wherever possible. In arable situations, this means looking at what operations are being carried out, are they all essential, how much fuel do they use, what alternatives might be available. Ensuring tyre pressures are appropriate for the type of work being carried out and making sure tools are adjusted correctly will also result in savings.

On the ruminant livestock side, taking animals to feed whether by grazing or self-feeding, rather than feed to animals will save fuel and often many other associated costs.