INTRODUCTION

For many combinable crop businesses, harvest 2017 will have produced some very good returns – possibly the best for some years. But often, this will be due to external factors, not least the weakness of Sterling, rather than the fundamental strength of the business itself. With so much uncertainty over future trading and support arrangements after Brexit, what should the sector do to prepare itself for the years ahead?

PRICES

For the past five harvests, the trend has been for ever-higher year-end global wheat stocks. Unsurprisingly, this has weighed heavily on world prices and global markets have slipped to 10-year lows in the past year. Early estimates for the 2018 harvest show a reversal of this trend with year-end stocks of wheat forecast to fall. Whilst the reduction is relatively small and might not be enough to boost markets much on its own, the overall global cereals market looks tighter too. For coarse grains (feed grains; mostly maize), forecast stocks following harvest 2018 will not have been so low since 2012. Markets seem relatively relaxed about this at present. But it offers the hope of an improvement in prices. If coarse grains prices rise, most other cereals follow suit – including wheat, the most import crop for UK growers. Strong global growth and a rising oil price also help to improve commodity prices, including ‘soft’ commodities like grains. UK grain prices have been insulated from the falls on the global market by the weakness of the Pound since mid-2016. This has added £15-£20 to the price of a tonne of feed wheat from what it would otherwise have been. Although the cold, wet, spring might reduce domestic output, it must be remembered that the UK is a fairly insignificant player in terms of global grains. Any price effects from lower yields will only be seen on a very local basis. Overall, there appears to be some potential ‘upside’ to prices for harvest 2018, but this is still very dependent on final yields achieved around the world and, of course, currency movements over the next few months.

POLICY

The Brexit negotiations grind on, with it being no clearer what the basis of the future trading relationship between the UK and EU is going to be. This is crucial to any sector that trades with Europe, including the cropping sector. The agreement on a ’transition period’ through to December 2020 at least means that sales from harvest 2019 will not face upheaval. More clarity is emerging around farm support after Brexit. The recent Defra consultation on the future of farming in England set out a clear path away from area based direct payments like the BPS. Whilst the BPS will continue to operate (probably unchanged) for 2019, a Domestic Agricultural Policy (DAP) looks set to be introduced for 2020. Area payments will not disappear overnight but will be gradually phased-out during an ‘agricultural transition’ – probably for five years. During this period payments to larger businesses may well be targeted through ‘capping’ or other mechanisms. Support will still be available, but it will shift to payments of ‘public money for public goods’. Public goods cover things such as biodiversity, landscapes, public access, water quality, soil health, flood prevention and animal welfare. The Government has committed to keep funding at present levels until 2022, but thereafter there are no guarantees. It is clear that farmers will be expected to jump through more hoops to receive support in future. All this will become clearer when the draft Agriculture Bill is published later in the autumn. The devolved administrations have been less forthcoming about future support – probably because how much of farm policy is to be devolved after Brexit has not been settled. However, the coming months will see their thoughts on future support start to emerge.

PROFITABILITY

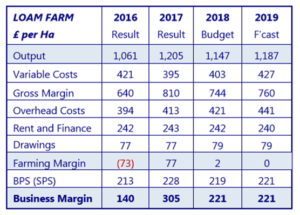

Since 1991, Andersons has been using its Loam Farm Model to track the fortunes of UK combinable cropping farms. It comprises 600 hectares in a simple rotation of milling wheat, oilseed rape, feed wheat and spring beans. The table shows figures for four harvests. Harvest 2017 showed an improvement on the previous year, mainly as a result of higher sale prices. Variable costs were down largely due to a dip in fertiliser prices. Overhead costs rose – partly as a result of higher fuel costs, but also because the cost of machinery has moved upwards. Even so, the business made a profit from its farming activity for the 2017 harvest. Add in a very favourable BPS payment, and the total business surplus is very good. This is the best overall return Loam Farm has seen since 2012. The prospects for the upcoming 2018 harvest are not quite as good – projected yields have been trimmed due to the late, wet spring. However, prices are still reasonable which helps the business just about break -even from its cropping operation. The budget for 2019 shows little change in the overall results. However, it can be noted that costs have risen (mainly fertiliser and machinery depreciation). This has been offset by budgeted yields reverting to normal levels.

BUSINESS MANAGEMENT

Loam Farm shows that returns from arable farming are about break-even if support is discounted. With costs rising, future trade uncertain, and support systems changing, many cropping businesses need to reassess their farming operations. The interaction of yields and costs is the key determinant of profitability. High yields will reduce the cost of production per tonne, but often the optimal level is not the highest level – accepting lower output for reduced input use, or more sustainable rotations is often a trade-off worth making. Similarly, simply not cropping the areas of the farm with the worst yield potential can make sense. The largest differences in costs are usually seen in overheads. Some farms will devote far less effort into efficient deployment of labour and machinery than they do into their agronomy programme. Great opportunities still exist for the industry to take out costs through increased cooperation and collaboration. High rents (or rent-equivalents) have added cost in many businesses. All parts of the sector need to take a realistic view of economically-sound rental levels, with an eye on future support changes and a long-term perspective on the husbandry of the land.

HELPING YOUR BUSINESS

The effects of Brexit look to have been delayed until 2020 in terms of support, and probably 2021 in terms of trade. It would therefore be easy to carry-on doing much the same thing in the short-term. However, change is undoubtably coming, and those businesses that grab a head-start in improving efficiency will be best placed to prosper in the new environment.

Andersons already work with some of the most progressive cereals businesses. Our consultants can help arable farmers make the correct strategic decisions and improve profitability.

Arable Outlook is provided in good faith for information purposes. No responsibility is taken by Andersons the Farm Business Consultants Ltd or its participating practices for any inaccuracies or omissions it contains. In all practical situations you are advised to take specific professional advice.